Quick Summary

PLA is not a “magic solution” to plastic waste. It performs best only when supported by industrial composting systems, clear collection programs, and the right applications. When used incorrectly, PLA can contaminate recycling streams and behave much like conventional plastics. Businesses should evaluate regulations, infrastructure, and product usage before deciding whether PLA is truly the right choice.

1. Introduction: PLA and the Global Plastic Crisis

Plastic waste is one of the defining environmental issues of our time.

Worldwide, millions of tons of plastic packaging are produced each year. A large percentage is used only once — particularly in foodservice, takeaway, supermarkets, catering, and e-commerce.

Despite recycling initiatives, the reality remains:

-

Much plastic still goes to landfill

-

A portion leaks into the environment

-

Recycling systems struggle with contamination and cost

-

Policymakers are tightening controls on single-use plastics

Within this context, PLA (Polylactic Acid) entered the conversation as a promising alternative. It sounds ideal:

-

Plant-based

-

“Biodegradable”

-

“Eco-friendly”

-

Marketed as a replacement for traditional plastics

But sustainability decisions cannot rely only on marketing language.

The critical question is:

Does using PLA genuinely reduce plastic waste, or does it simply shift environmental burdens from one place to another?

This article examines PLA from an operational, scientific, and practical buyer perspective.

Our goal is not to promote or criticize PLA — but to understand how it works in the real world, where it succeeds, and where expectations exceed reality.

2. What PLA Actually Is — and Why It Matters

PLA is a bio-based thermoplastic polymer produced from renewable feedstocks such as:

-

Corn starch

-

Sugarcane

-

Cassava

-

Other agricultural sugars

The basic process:

-

Starch or sugars are converted into lactic acid through fermentation.

-

Lactic acid molecules are polymerized into polylactic acid.

-

PLA is pelletized, transported, and converted into finished products.

Common PLA applications in packaging include:

-

Cutlery and tableware

-

Flexible films

-

Portion cups

-

Food trays (cold applications)

From a performance viewpoint, PLA offers:

| Attribute | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Transparency | Similar to PET, visually appealing |

| Rigidity | Better than PS in some forms |

| Odor | Neutral |

| Weight | Lightweight |

| Origin | Renewable feedstock |

However, PLA differs sharply from conventional plastics:

-

Heat resistance is limited (typically 45–60°C)

-

Exposure to heat can deform and warp

-

Not microwave-safe

-

Not compatible with hot-fill operations

-

Not designed for traditional recycling streams

Understanding these boundaries is essential before selecting PLA.

3. The Expectations Behind PLA Adoption

Many stakeholders — retailers, brands, restaurants, and consumers — associate PLA with environmental benefits because it is plant-based and marketed as compostable.

Typical assumptions include:

Assumption 1: “PLA disappears quickly after disposal”

People imagine PLA breaking down like food waste or paper.

In reality, degradation depends entirely on controlled conditions.

Assumption 2: “PLA automatically reduces plastic waste”

Replacing plastic with PLA does not guarantee lower waste unless the disposal pathway is well-designed.

Assumption 3: “PLA is recyclable”

Most municipal recycling systems do not accept PLA, and when it enters PET streams, it creates contamination.

Assumption 4: “Composting is easy and universal”

Industrial composting capacity varies dramatically from region to region — and is nonexistent in many developing markets.

4. The Science: How PLA Degrades (and When It Does Not)

PLA degradation is not magic. It is chemistry.

For PLA to break down efficiently, it must enter industrial composting, where:

-

Temperature reaches 55–60°C

-

Humidity is managed

-

Oxygen levels remain stable

-

Microorganisms actively break down polymers

Under those controlled conditions, PLA can decompose over weeks to months.

But when PLA is:

-

Landfilled

-

Mixed into household trash

-

Disposed into natural environments

-

Stored in dry, cool conditions

it behaves very similarly to conventional plastics — remaining intact for long periods.

Meaning:

PLA is “conditionally compostable,” not universally biodegradable.

This is a critical nuance often missed in marketing.

5. Where PLA Genuinely Performs Well

PLA can contribute to sustainability when aligned with infrastructure and policy.

(1) Closed and controlled systems

PLA is effective when products are collected separately and directed to composting, such as:

-

Corporate cafeterias

-

University dining halls

-

Airport food courts

-

Music festivals with managed waste streams

-

Events with clear signage and training

In these controlled systems, waste planners can ensure PLA goes where it should.

(2) Markets prioritizing compostable packaging

Certain municipalities and regions support composting programs that:

-

Accept food waste and certified compostable packaging together

-

Reduce landfill volume

-

Produce compost for agriculture and landscaping

In those systems, PLA can be part of a broader organic recycling strategy.

(3) Lifecycle improvements

Because PLA is plant-derived, it can offer environmental advantages at the production phase:

-

Reduced fossil resource dependence

-

Lower greenhouse gas emissions (under certain production models)

-

Support for biomass production initiatives

But again, lifecycle results depend heavily on local supply chains and energy sources.

6. Where PLA Creates Hidden Risks

PLA can unintentionally increase environmental burdens when:

1. It enters landfills or nature

Composting conditions do not exist.

2. It contaminates recycling streams

Recyclers must separate PLA manually, incur additional costs, and sometimes discard entire batches.

3. It is mislabeled or poorly communicated

Consumers misunderstand disposal instructions.

4. Businesses rely on PLA alone

Replacing plastic without addressing consumption levels does little to change total waste output.

5. Food residue remains

Contamination complicates composting or disposal routes.

The takeaway:

PLA is only as sustainable as the waste-management ecosystem supporting it.

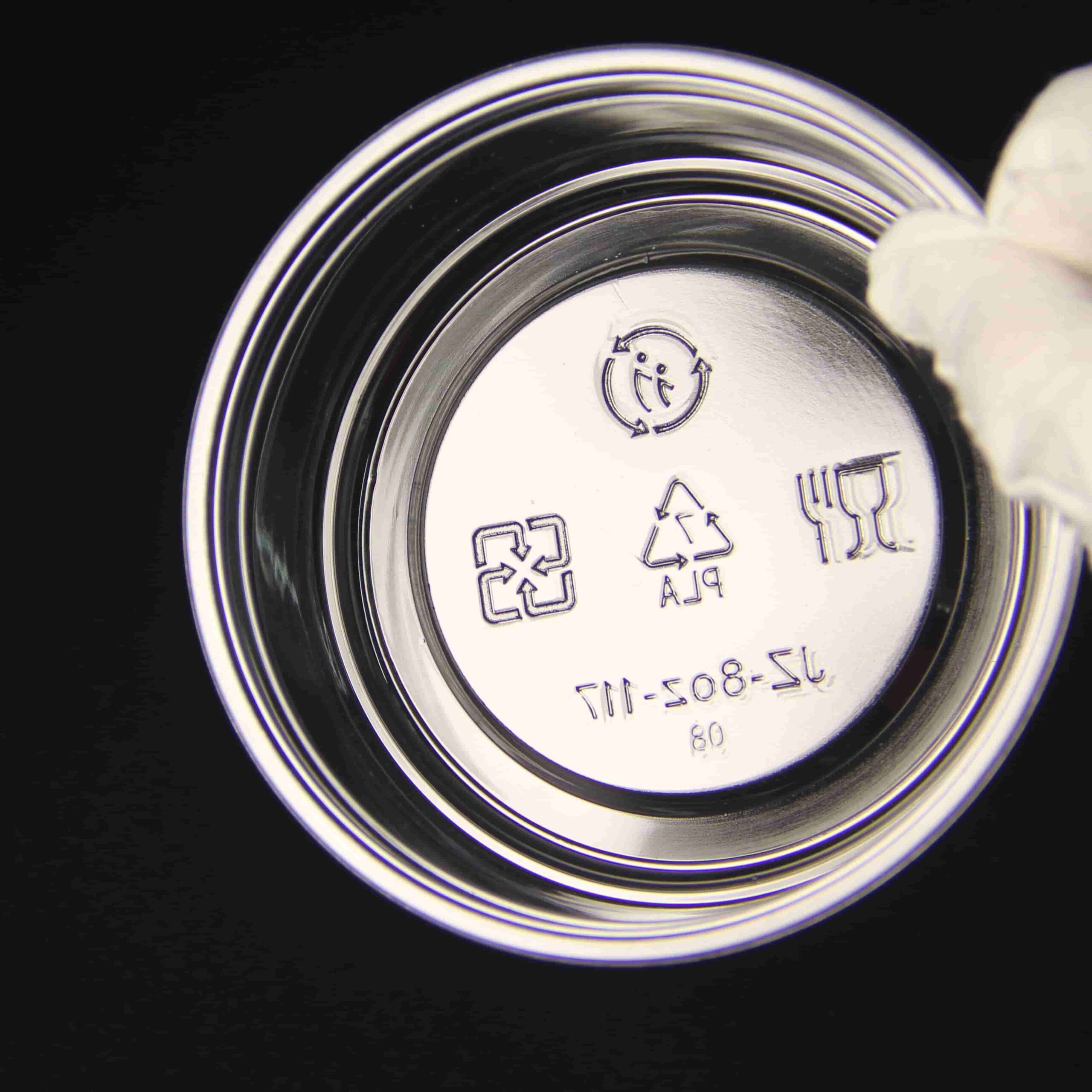

7. Understanding “Biodegradable” vs “Compostable” — Without Confusion

Many buyers misinterpret labels. Clear definitions matter.

Biodegradable:

Breaks down through microbes at some point, somewhere, under undefined conditions.

Compostable:

Must break down within defined timeframes under composting conditions, leaving no toxic residue.

Key standards include:

-

EN 13432

-

ASTM D6400

-

ISO 17088

A responsible supplier should be able to show documentation — not just claims.

8. When PLA Truly Helps Reduce Plastic Waste — Practical Scenarios

PLA adds value when:

-

Foodservice generates mostly organic waste

-

Compostable packaging supports food-waste diversion

-

Collection programs exist

-

Consumers receive clear disposal guidance

-

Operators track and monitor outcomes

-

Product design avoids mixing multiple materials

Example strategies:

-

Using PLA cups alongside food-waste composting bins

-

Training staff to separate PLA effectively

-

Partnering with local composting facilities

-

Clear on-pack communication (“Industrial composting only”)

When done properly, PLA becomes part of a closed-loop approach.

9. When PLA Does NOT Help — and May Undermine Sustainability

PLA becomes problematic when:

-

Chosen only for marketing reasons

-

Used in regions without composting systems

-

Added to multi-material packaging (hard to process)

-

End users receive no disposal education

-

Hot-food applications deform the product

-

Alternative materials (PP, RPET, paper) would perform better

In such cases, PLA does not replace waste — it simply changes the type of waste.

10. Practical Framework for Buyers, Importers, and Brands

Before deciding on PLA, businesses should evaluate:

A. Regulatory alignment

Are local authorities encouraging compostable packaging?

B. Infrastructure readiness

Is there access to industrial composting or organics collection?

C. Application suitability

Will the product face heat, grease, or heavy loads?

D. Lifecycle trade-offs

Does PLA truly outperform alternative materials here?

E. Labeling responsibility

Will customers receive accurate disposal instructions?

Adopting PLA without these considerations creates risk.

11. How Responsible Suppliers Can Help (DASHAN Example Insight)

Responsible manufacturers play a key role in preventing misuse.

At DASHAN, when customers inquire about PLA, we typically:

-

Clarify intended market regulations

-

Evaluate end-use environments

-

Suggest alternative materials when PLA is unsuitable

-

Help customers build labeling guidance and compliance references

-

Discuss compostability certifications honestly — without exaggeration

PLA is one tool in a broader sustainability toolkit, not a one-size-fits-all answer.

12. The Future of PLA and Bio-Based Packaging

Looking ahead, industry trends indicate:

-

Improvement in PLA performance and blends

-

Growth of composting infrastructure in select markets

-

Expansion of corporate sustainability commitments

-

More transparent certification enforcement

PLA will not eliminate plastic waste, but it can contribute to smarter, circular packaging design where conditions support it.

FAQ

1. Is PLA really biodegradable?

Yes — but only under specific conditions. PLA needs industrial composting environments with controlled heat, moisture, and oxygen. In landfills or nature, it may break down very slowly.

2. Can PLA be recycled with other plastics?

No. PLA should not enter PET or mixed plastic recycling streams. It can cause contamination and disposal problems.

3. Does switching to PLA always reduce environmental impact?

Not always. PLA helps only when supported by composting systems and proper waste sorting. Without infrastructure, it may perform similarly to traditional plastics.

4. Is PLA safe for hot food and microwaves?

Generally no. Most PLA softens at 45–60°C and is not suitable for hot meals, microwaves, or ovens.

5. What certifications should I look for?

Look for compostability standards such as:

-

EN 13432

-

ASTM D6400

-

ISO 17088

These prove PLA has been tested under defined composting conditions.

6. When should businesses choose PLA?

PLA makes sense when:

-

Food waste and packaging are collected together

-

Industrial composting exists locally

-

The application is cold or room temperature

-

Labels and education clearly explain disposal

7. When should businesses avoid PLA?

Avoid PLA if:

-

No composting infrastructure exists

-

Products will face high heat

-

Packaging mixes multiple incompatible materials

-

Recycling contamination risk is high

Conclusion

PLA is not a miracle environmental solution.

But when implemented responsibly — in the right markets, with the right products, and within systems that support composting — PLA can indeed:

-

Reduce dependence on fossil plastics

-

Support food-waste collection strategies

-

Improve environmental performance across select applications

The key is not simply choosing PLA.

The key is asking:

“Does our system support PLA — from supply to disposal?”

Only then does PLA meaningfully contribute to reducing plastic waste.

References

-

Ellen MacArthur Foundation — New Plastics Economy

https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/new-plastics-economy -

European Commission — Bio-based and Biodegradable Plastics

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/plastics/bio-based-and-biodegradable-plastics_en -

ASTM International — Compostable Plastics Overview

-

U.S. EPA — Plastics: Material-Specific Data

https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/plastics-material-specific-data -

NatureWorks (Technical Resources on PLA)

https://www.natureworksllc.com/What-is-Ingeo

Copyright Statement

© 2026 Dashan Packing. All rights reserved.

This article is an original work created by the Dashan Packing editorial team.

All text, data, and images are the result of our independent research, industry experience,

and product development insights. Reproduction or redistribution of any part of this content

without written permission is strictly prohibited.

Dashan Packing is committed to providing accurate, evidence-based information and

to upholding transparency, originality, and compliance with global intellectual property standards.