Core Thesis

Food delivery packaging has evolved from functional protection into visual theatre. In pursuit of “premium” aesthetics, brands now layer materials, sleeves, and decorative wraps far beyond necessity—creating systems that are costly, complex to recycle, and environmentally unsustainable. DaShan argues for a return to performance-based packaging design—where every gram serves a purpose and every material has a clear end-of-life.

Why It Matters

Packaging accounts for roughly 40% of global plastic waste, according to OECD’s Global Plastics Outlook (2024). The rapid growth of food delivery has intensified this challenge: more single-use items, more mixed materials, and more confusion over disposal. As overpackaging becomes normalized, we risk multiplying waste streams that cities cannot handle—and undermining genuine sustainability efforts.

Action Agenda

-

Redefine “premium” by functionality, not aesthetics.

-

Limit component count per order and simplify materials.

-

Make packaging fees transparent.

-

Prioritize mono-material and PFAS-free designs.

-

Align design claims with local end-of-life realities.

-

Promote consumer choice: allow opt-out for extras.

1. Introduction — The Hidden Cost of Visual Luxury

In major cities from Shanghai to San Francisco, food delivery has become an integral part of urban living. Yet, what used to be a practical vessel for meals has evolved into a packaging performance—rigid boxes, embossed sleeves, thank-you cards, cutlery kits, and multi-layered bags. Each element aims to make the experience feel “premium.”

But behind this curated unboxing moment lies a paradox: higher waste, higher cost, and lower recyclability.

What began as a brand differentiator has morphed into a sustainability liability. Restaurants and delivery platforms now compete visually, not functionally—driving an “arms race” of decorative materials that neither improve food quality nor protect the planet.

2. From Craft to Costume — How Aesthetic Obsession Took Over

2.1. The Cultural Roots of Presentation

Japan’s refined packaging culture—rooted in gift-giving and ceremony—has long celebrated presentation. Transposed to modern takeout, however, these principles have been exaggerated: multiple layers, plastic laminations, and ornamental details intended to elevate perceived value.

2.2. China’s Rapid Shift to “Branded Kits”

Over the last decade, China’s takeaway sector transformed from simple PP boxes and transparent lids to multi-component branded kits. Custom sleeves, kraft wraps, and decorative inserts became common, particularly among chain restaurants. This visual inflation turned packaging into a marketing tool rather than a practical safeguard.

2.3. The Global “Eco-Luxury” Paradox

The international “eco-look”—matte kraft, foil-free prints, and layered paper wraps—often signals sustainability while defeating it. Behind the minimalist facade are non-recyclable laminates, coatings, and hidden plastics that render the entire package unsuitable for composting or recycling.

The result: a product that looks eco-friendly but performs poorly in waste systems.

3. The Measurable Impact — Five Dimensions of Overpackaging

3.1. Component Explosion

A single entrée can generate up to 10 packaging items: base, lid, sleeve, cup, insert, outer bag, cutlery, and label. Each addition raises material use, assembly time, and disposal complexity.

3.2. Material Mixing

Most “premium” delivery boxes combine paperboard with PE film or foil for oil resistance—an inseparable mix. Recycling facilities reject such hybrids, sending them to landfill or incineration.

3.3. Volume Inefficiency

Empty space is the silent emitter. Oversized boxes consume more freight capacity and storage space, contributing to avoidable CO₂ emissions in delivery logistics.

3.4. Economic Distortion

Consumers often pay for “presentation layers” disguised as “service fees.” Without transparency, the food–packaging ratio in pricing becomes opaque, eroding trust.

3.5. Performance Failure

Ironically, many “luxury” kits perform worse. Broth leaks, steam traps, and soggy textures remain top complaints in delivery reviews, showing that aesthetics do not guarantee function.

4. Who Bears the Cost?

| Stakeholder | Impact | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Consumers | Cost & confusion | Higher prices, more clutter, unclear disposal routes |

| Restaurants | Margin erosion | Decorative grams add costs without improving food quality |

| Municipalities | Waste burden | Overpackaging inflates collection costs and contamination |

| Environment | Resource loss | More plastic, paper, and coating materials used per calorie delivered |

The conclusion is clear: everyone pays, but no one benefits proportionally.

5. Policy and Market Evidence (2024–2025)

-

OECD and UNEP agree: packaging dominates global plastic waste streams (~40%).

-

EU’s Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) demands recyclable or reusable packaging by 2030.

-

The U.S. FDA and EU ECHA have both advanced PFAS phase-outs in food-contact packaging.

-

Asian cities including Seoul, Taipei, and Singapore are piloting EPR-based fee structures that penalize non-recyclable materials.

The direction is unmistakable: simpler, cleaner, mono-material packaging is the future.

6. Diagnosing Overpackaging — A Functional Checklist

| Metric | Target | Problem Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Unit count per order | ≤3 major items | ≥6 shows redundancy |

| Material types | ≤2 | ≥4 indicates mixed waste |

| Separation ease | <5s | Laminated, glued, or foiled parts |

| Volume fit | ≤15% empty space | Oversized boxes |

| PFAS status | Verified free | Unknown or untested |

DaShan uses this diagnostic framework to help clients audit existing packaging portfolios and identify reduction opportunities.

7. The DaShan Approach — Redesigning for Function, Not Ornament

DaShan’s philosophy begins with a simple principle: form follows function.

Each product is engineered to maximize protection, minimize material use, and align with real-world recovery systems.

7.1. PET Sushi Trays — Clarity Meets Circularity

DaShan’s Square PET Sushi Trays combine transparency with rigidity. They showcase food beautifully while using mono-material PET, ensuring high recyclability. Their tight-fit lids prevent leaks without secondary wraps or sleeves, achieving visual appeal through clarity, not complexity.

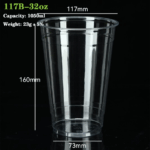

7.2. PLA Cold Drink Cups — Compostable Convenience

Made from PLA (polylactic acid) derived from renewable corn starch, DaShan’s cold drink cups offer a biodegradable alternative for beverages. Designed strictly for cold drinks (not hot), they reduce plastic reliance while remaining optically clear and brandable. Paired with flat or dome lids, they deliver function without overdesign.

7.3. CPET Airline Meal Trays — Heat-Ready and Durable

For hot meal applications, DaShan’s CPET trays withstand temperatures up to 220°C, suitable for airline catering and oven reheating. Their dual-temperature resilience (from freezer to oven) eliminates the need for secondary containers, significantly cutting material layers per meal.

7.4. RPET Fruit Containers — Recycled, Recyclable, Responsible

DaShan’s RPET fruit boxes embody the company’s circular design ethos: made from post-consumer recycled plastic, they close the loop by being recyclable again. Their ventilated structure minimizes condensation and waste, proving that eco-design and shelf appeal can coexist.

8. A Multi-Stakeholder Pathway to Reform

8.1. Consumers

-

Demand “necessary packaging” options.

-

Opt-out of cutlery or extra layers during checkout.

-

Rate positively when minimal, efficient packaging performs well.

8.2. Restaurants & Brands

-

Prioritize function validation (heat, leak, and vent testing).

-

Limit SKUs and unit counts.

-

Choose suppliers with verified PFAS-free and recyclable materials.

8.3. Platforms & Regulators

-

Enforce transparency in packaging fees.

-

Cap unit counts per order.

-

Mandate truth-in-labeling based on local recycling capabilities.

8.4. Packaging Manufacturers

-

Simplify design: one base + one lid = standard.

-

Provide batch-linked testing data for safety and recyclability.

-

Adopt mono-material and structural barrier strategies instead of coatings.

9. Evidence-Informed Tools for Packaging Reduction

Table 1 — Overpackaging Risk Matrix (0–3 per factor)

| Factor | 0 (Low) | 1 | 2 | 3 (High) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit count | ≤3 | 4–5 | 6–7 | ≥8 |

| Material diversity | ≤2 | 3 | 4 | ≥5 |

| Separation time | ≤5s | 6–10s | 11–20s | >20s |

| Coating intensity | Structural | Light | Heavy | Laminated |

| PFAS risk | Verified-free | Transition | Unknown | Likely present |

👉 Total Score ≤6 = Acceptable; 7–12 = Review; ≥13 = Redesign Immediately.

Table 2 — Redesign Reference Guide

| Goal | Smart Design (Do) | Overpackaged Design (Avoid) |

|---|---|---|

| Leak control | Ribbed rims, sealed lids | Double-boxing |

| Heat control | Vent holes, CPET base | Foil-lined paper |

| Brand identity | Clear PET lid, logo emboss | Multi-layer sleeve |

| End-of-life | Mono-material structure | Plastic-coated paper |

| Consumer convenience | Simple disposal | Confusing materials |

10. Looking Ahead — Policy & Market Evolution (2025–2030)

-

EPR Expansion: Producers will pay variable fees based on recoverability and toxicity.

-

PFAS Bans: Complete elimination in food-contact packaging across EU and North America.

-

Design for Recycling: ISO 18606 and PPWR require traceable mono-material packaging.

-

Consumer Education: Apps and QR codes linking to disposal guides will become standard.

-

Sustainability Verification: Audited claims will replace “green” self-declarations.

DaShan’s R&D roadmap aligns directly with these global trends—preparing today for tomorrow’s compliance.

11. Responsible Aesthetics — Beauty that Performs

A sustainable aesthetic doesn’t mean dull packaging. It means purposeful beauty—where elegance meets efficiency.

DaShan demonstrates this through minimalist geometry, transparent lids, and functional textures that communicate quality without excess.

Modern consumers are increasingly drawn to “honest design”: clean, lightweight, recyclable, and informative. This is the next visual language of food packaging—clarity over clutter.

12. The Call — From Overdesign to Oversight

The overpackaging problem isn’t about villainizing aesthetics—it’s about reclaiming proportion.

-

For consumers: Choose simplicity; value food over wrapping.

-

For restaurants: Prioritize product integrity and sustainability metrics.

-

For regulators: Incentivize less, not more.

-

For suppliers like DaShan: Lead by proof—PFAS-free, recyclable, and responsibly sourced.

When beauty aligns with function, packaging becomes invisible again—quietly doing its job.

13. DaShan — The Commitment Behind Every Container

At DaShan, we believe sustainability starts with clarity and consistency.

Our packaging solutions—from PET sushi trays to RPET fruit containers, PLA cups, and CPET airline trays—embody a singular vision:

protect the food, respect the planet.

Each DaShan product is engineered to minimize components, maximize performance, and ensure recyclability or compostability within real-world systems. We back every claim with verified testing—PFAS-free certification, migration reports, and recyclability data.

We are redefining packaging not as a visual accessory, but as a responsible bridge between the kitchen and the customer.

Because the best packaging doesn’t steal attention—it earns trust.

FAQ — Overpackaging and Sustainable Food Delivery Design

1. What is overpackaging in food delivery?

Overpackaging refers to using excessive or unnecessary packaging materials in food delivery, often for visual appeal or branding. It increases waste and environmental impact.

2. Why is overpackaging harmful to sustainability?

It leads to more plastic waste, higher carbon emissions, and energy use in production and disposal. Overpackaging also complicates recycling and increases operational costs.

3. How does DaShan promote responsible packaging design?

DaShan develops smart, eco-friendly packaging like PET sushi trays, PLA cold drink cups, CPET airline meal trays, and RPET fruit containers—balancing aesthetics with performance and sustainability.

4. What are current regulations addressing overpackaging?

The EU’s PPWR (Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation) and similar policies worldwide aim to reduce excessive packaging, improve recyclability, and ban harmful substances such as PFAS.

5. How can food brands reduce overpackaging?

Brands can use lightweight, recyclable, or compostable materials, optimize design for function rather than decoration, and partner with responsible suppliers like DaShan for sustainable solutions.

Conclusion — Designing Proportion Back Into Packaging

Overpackaging is not innovation—it’s a misdirection.

True progress in food delivery packaging lies in engineering precision, transparent communication, and end-of-life responsibility.

The future belongs to brands that deliver meals—not waste—and to suppliers like DaShan, who turn responsible design into standard practice.

References

-

DaShan Packaging (2025). Sustainable Food Packaging Insights: Smart Design for a Circular Economy.

https://www.dashanpacking.com/sustainable-food-packaging-insights/ -

European Commission (2025). Packaging Waste and Circular Economy Action Plan.

https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/packaging-waste_en -

Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2024). Rethinking Packaging: Towards a New Plastics Economy.

https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/the-new-plastics-economy -

Packaging Europe (2025). The Reality of Overpackaging in Food Delivery Services.

https://packagingeurope.com/features/the-reality-of-overpackaging-in-food-delivery/

Disclaimer & Copyright Notice

This article is created by the Dashan Packing editorial and research team.All information presented here is for educational and industry reference purposes only.Some data and standards cited in this article are sourced from publicly available materials,official regulatory documents, or third-party publications, which are properly credited where applicable.

All rights to third-party trademarks, images, and content belong to their respective owners.If any copyrighted material has been used inadvertently, please contact us at angel@chndashan.com.We respect intellectual property rights and will promptly remove or revise any material upon verification.